The Arctic Convoy Club

of New Zealand

Veterans of the Arctic Convoys 1941 - 1945

Bill Brokenshaw : HMS Chiltern : My Story

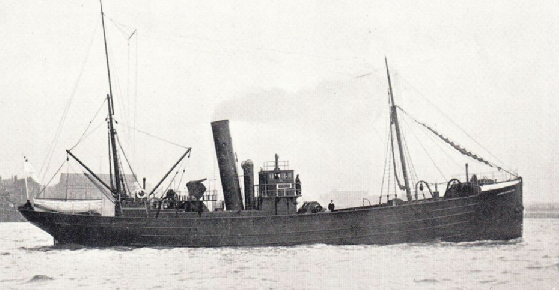

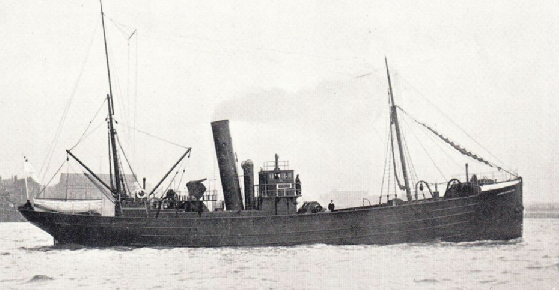

I joined the trawler Chiltern in February 1940 at Fleetwood starting off as Decky Trimmer helping to shovel ten tons of coal a day. In June 1940 our Skipper was ordered to pack up fishing and to proceed to St Nazaire to help with the evacuation of French people, mostly women and children. The place was absolutely chaotic. Everyone was trying to get aboard the vessels that were in the port. While we were there the troopship “Lancaster” was blown up with much loss of life. We eventually left with our trawler carrying 300 evacuees. We proceeded to Millbay in Plymouth where all the French people left the trawler. After a few days leave we found we had been taken over by the Royal Navy. It looked as if our fishing days were over - we were converted into a minesweeper. Evidently the Chiltern had done minesweeping in 1917 when she had been built.

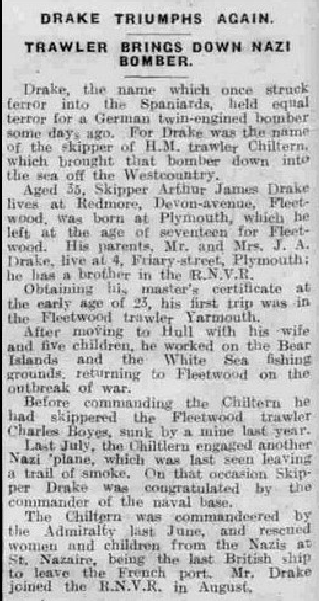

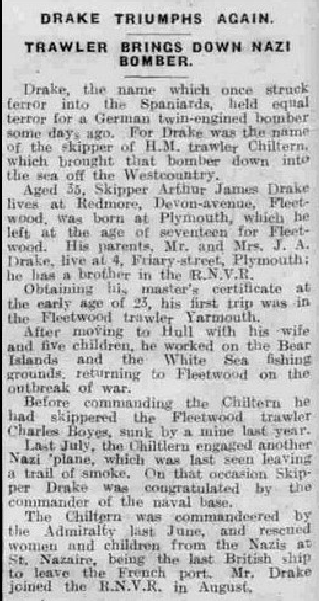

For the next 18 months we swept the Cornish and Devonshire coasts “collecting 47 mines in 20 weeks. Up to one third of our trawlers were lost to mines and enemy aircraft. On 28 May 1941 at approximately 2200 hrs while we were approaching our anchorage in Mounts Bay, Penzance, during an air raid a German bomber came within our range. With just one shell we were able to bring it down.

Life aboard our trawler was not the best. Ice, snow, freezing winds, everything wet, no sleep. Only warm place was in the stokehole with the fireman. Our clothing wasn’t really suitable for those sort of conditions but there was a lot worse to come. We were to spend the next 16 months in those Northern waters. Summer was May to August when one would actually see sunshine. The rest of the year was gales, snow and ice. German aircraft made the most of the summer months. They came from Petsamo (Petchenga) Finland and averaged about ten air raids a day. Many of the buildings in Murmansk were built of timber. Dropping incendiary bombs set fire to the whole city over a period of days. When we left Murmansk in August 1943 the city was as flat as football field. One radio station said there had been over 1,000 bombing attacks since the war started. We must have seen two thirds of them.

One of the worst times was four days and nights we laid across the end of the jetty at Murmansk waiting for a tug to take us to Vaenga on the Kola Inlet where a new propeller was to be fitted. Bombs were dropping in the sea on one side of us and on the land on the other side of us. One of the more terrifying experiences of my time in Russia. (Our mate up topside must have been looking after us during that time). It was certainly sheer hell. We eventually, with the help of a third of a propeller blade made our way to dry dock. Must have done all of two knots with the help of an outgoing tide. Now, a funny side to the story. The Russians fitted a new propeller with a reverse pitch. This meant when the engines were put ahead the ship went astern and vice-versa. One of the men came up with a little verse:

The Chiltern they tell me acquired

A propeller they truly admired

But, in utter disgrace

It was ass about face

And instead of advancing, retired

While we were having these repairs done we sometimes went for a walk away from the dockyard. One day we came across a small cemetery. I noticed several graves marked with crosses. It turned out that they were the graves of British soldiers that Churchill had sent to Russia in 1917. I wish now that I had taken the details of those men buried there.

Convoys came and convoys went. The Chiltern was always around providing a helping hand. Unloading stores, taking RN and merchantmen to the local hospital at Vaenga. Some of these men were in a terrible state with frostbite, their ship sunk under them or caught in an air raid. In May 1942 there were 1,100 survivors from HMS Edinburgh, HMS Trinidad and merchantmen from PQ15. Our next convoy was PQ17 of which much has been written but which, at the time, we did not know much about. Sufficient to say the Germans were free to pick off our merchant ships one at a time. Chiltern was ordered to look for survivors. All we found were 83 American and British sailor boys whose ships were caught up in the ice. We had the help of a Catalina flying boat to find them. Life was never dull in those Northern waters. The “Empire Starlight” was another ship that was bombed and sunk in the Kola Inlet after she had discharged her cargo.

This website is owned by The Arctic Convoy Club of New Zealand © 2004 - 2024

This page updated August 2024

This site uses images in SVG file format.

For best viewing results, please ensure you are using the latest version of your web browser.

Although the crew of the aircraft were able to release their life raft they were not able to save themselves. We picked up their life raft and a new type of radio was found which was capable of sending the position of a disabled aircraft which could be rescued. HMS Chiltern made headlines in the local papers and we were visited by the Air Marshall of the Royal Air Force. Skipper Jimmy Drake was now Lieutenant James Drake, RNR but to us he was always “Jimmy”.

In December 1941 we had orders to proceed to a South Wales shipyard where we had another refit preparing us to go to North Russia to fish for the convoys at the Northern base of Polyarnoe. We left Cardiff on Sunday the 15 February 1942 and went to Greenwich where we took on three months stores and fresh water. The 26 February saw us in the North Atlantic sailing for Iceland. We were all looking forward to seeing Reykjavik. Sorry to say we hit uncharted rocks on 3 March and had to go up on a slipway. I ended up in hospital for several days with some undiagnosed ailment. I wonder why!?! The chap in the next bed was in a coma for 21 days!

We set sail with PQ13 on Monday 8 April. Twenty six ships in the convoy. Snowing very hard. Visibility down to about 50 yards. We were ordered to return to port. Set off again 26 April 1942 with PQ15. We ran into fog, snow and ice once we were in the Arctic Circle. Following day spotted two floating mines and heard gunfire from one of our ships. On the 1 May two German aircraft were shot down. The 2 May enemy attacked the convoy, one sub captured and on 3 May convoy attacked by many torpedo bombers four times. Three ships were torpedoed. The Chiltern picked up 62 men off one ship, (the Jutland), including four RAF officers going to Murmansk to train Russians to fly Spitfires and Hurricanes, and members of the British Embassy staff going to Moscow. Six other members of the crew were missing. One aircraft came down across our stern firing his machine gun missing us by about ten feet. Another of our “lucky days”. An American tanker full of high octane fuel was hit and blew up in seven seconds. Another “Woodbine” funnel had to be sunk by one of our Naval ships.

A Commander Cole, who was in charge of the 100 men at the Navy house in Polyarnoe came aboard us to ask us to take him aboard what was left of the “Empire Starlight” which could be boarded at low tide. He wanted everything that could be salvaged taken off to go to Navy house. He said if there should be an air raid he would blow his whistle three times and we would all assemble aft of the bridge. Time went by and our crew seemed to be solely concerned with what they could take for themselves (the spoils of war?). Eventually the whistle sounded and we all hastened to assemble aft. No sign of an aircraft or an air raid. Then the Commander addressed us. “Gentlemen” he said “ this petty pilfering, this individual scrounging must cease”. Oh boy, what a shock. However, he was very fair and said “Get what I want and the rest of the ship is yours”. One very sad part was I was asked to go aft and bring back some cork fenders. Unfortunately there were a number of bodies trapped under them. I was 19 years old at the that time. “Lest we forget”. There is never any fear of that happening in my life time. Another time we had orders to pick up mail from HMS Gossamer. We were 20 minutes late and arrived to find mail and bodies in the sea. Twenty minutes between two of life's happenings.