The Arctic Convoy Club

of New Zealand

Veterans of the Arctic Convoys 1941 -

Peter Holt : HMS Tyne / HMS Scylla / HMS Belfast : My Story

1942 -

My new life in the Navy proper started in the bleak fleet anchorage of Scapa Flow, separated from the Scottish mainland by the notorious Pentland Firth. There I joined the destroyer depot ship HMS Tyne. She was a purpose built, recently launched ship designed to provide workshops and various other amenities for the dozens of destroyers operating with the Home Fleet. Thus she was a fairly comfortable ship to live in. The radio staff which now included me, handled the routine radio traffic on a three watch basis (4 hours on and 8 hours off). The ‘sparkers’ were run by a diminutive and bombastic Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist named Cooper. The ship housed and flew the flag of Rear Admiral Destroyers (RA(D)) when he was not at sea in some other temporary flagship. For the whole of my time in the Tyne, RA(D) was a fascinating little ex-

It was during this time that I met another young man who was to become a lifelong friend Ken (Wiggy) Bennett. By way of explanation I should point out that there is a wide range of nicknames current in the RN many associated with particular surnames e.g. "Nobby" Clark; "Wiggy" Bennett; "Chalky" White etc. When I joined Tyne, Ken was already there as a more senior and more experienced "sparker". We clicked intellectually, argued interminably about religion, both enjoyed good music and became good friends. Oddly enough I don't think we ever went to sea together in the same ship. But between us we became involved in many of the now historic episodes of the saga of the North Russian convoys either on RA(D)'s staff or lent to ships short of staff.

I served in HMS Tyne from 5th August 1942 to 20th October 1943. During this time I was lent to the destroyers HMS Middleton, HMS Intrepid and HMS Onslaught as a sparker and on each occasion for a convoy to North Russia usually via Iceland. Middleton, a Hunt class destroyer, was my first sea trip. As we left Scapa Flow in a strong westerly gale she rolled her guts out and I well recall the bleak misery of being hideously cold and frantically seasick. My seasickness lasted for three days. We were in two watches (four hours on four hours off) and I recall spending much of my time off watch standing on a heaving deck with my back to the funnel for warmth. Life on the forward messdeck of a destroyer left much to be desired. We were on what was called ‘Canteen Messing" where food was purchased by each mess from the Canteen, prepared by off watch members of the mess and communally cooked in the ship's galley. At the end of three days of being sick, I was urgently needing food and I recall that the midday meal consisted of cold overcooked roast beef bread and pickles. This seemed to do the trick and I am happy to say that since 1942, I have never again suffered from seasickness.

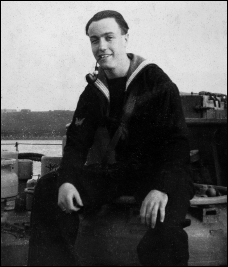

Peter Wilfred Holt on the HMS Tyne, 1942

I suppose that this convoy was really my baptism of fire and being on the Admiral's staff meant that one was in the hub of things. If you ever want to read about those stirring times read the following books which we have in paperback:

‘Convoy PQ18: Arctic Victory’ by Peter C Smith

‘Flagship to Murmank’’ by Robert Hughes J P

‘Very Ordinary Seaman’ by W Mallalieu

‘The Russian Convoys’ by B B Schofield

‘The Kola Run’ by Ian Campbell & Donald MacIntyre

In between the long hauls to North Russia we were kept occupied in the good ship Tyne in Scapa Flow. This anchorage is set in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland. In winter or bad weather they can be appallingly bleak and unwelcoming. On the other hand, in the summer months these can really be island of enchantment. I still have a vivid memory of a run ashore on the island of Hoy with Ken Bennett. It was wonderfully warm and we tramped over gentle hills and finally found ourselves beside a small lake. Because of the peat, the water was nearly red, but on a hot summer's day was extremely inviting. Stripping off, I was the first to get into the cool water. When I looked back, Ken was in near hysterics because whilst I had a bright red top (having unwisely slept in the sun on Tyne's foc'sle) my naked nether regions were ashen white! From where he sat it looked hilarious! After a refreshing dip we slowly made our way back to the jetty singing at the tops of our voices (the Overture from William Tell and other light classics). A glorious period of peace in an otherwise lively existence.

On another occasion Ken and I were detailed off to equip ourselves with a bulky portable radio transmitter and to accompany an Army Officer who was to act as spotting officer ashore for a flotilla of four new Hunt class destroyers who were to carry out a bombardment on the island of Papa Westray. We were landed by boat on the island and climbed up to a position where we could see the fall of shot from the destroyers. Our job was to send our officer's observations by wireless telegraphy to the ships. Eventually the ships were recalled to Scapa in some sort of an emergency and left at high speed, leaving the three of us stranded on the island. We walked some way to a crofter's cottage and our officer was able to use a telephone to make the authorities in Scapa aware of our predicament. Whilst waiting to be picked up we were fed by the crofter and before we left were presented with a sackful of live, very wriggly crabs! Getting off the island was very exciting as the Navy sent an amphibious Sea Otter aircraft to pick us up. The fishermen rowed us out to the aircraft and we piled in behind the aircrew still clutching our sack of crabs. I think it was the first flying experience for both of us. The plane landed in the water at Kirkwall and I recall that the Admiral's barge (a very sexy motor launch) picked us up and took us back to the Tyne. We lugged ourselves, our radio and our sack of crabs up the long starboard ladder and were back on board at last. If I remember correctly Chiefy Cooper got the crabs which were very welcome in the Chief Petty Officers' Mess.

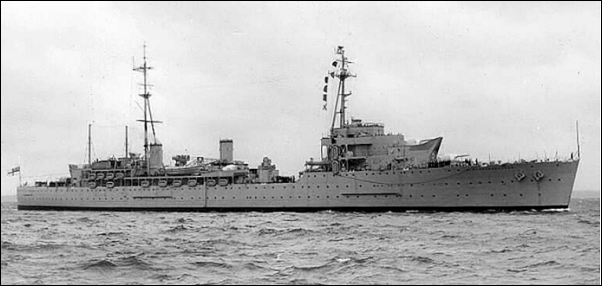

I also went with RA(D) to the cruiser Scylla for the September 1942 convoy PQ18. This was the first convoy to run to Russia after the infamous PQ17 in the June of '42. PQ17 marked the nadir of allied fortunes with the loss of many merchant ships following an Admiralty decision to scatter the convoy. PQ18, on the other hand, marked the beginning of a new era in these convoys when, for the first time we were able to match the Germans with comparable forces. Apart from Scylla which was a very modern anti-

For a very young telegraphist, these were heady days. We didn't have it all our own way though and there were some fairly hairy moments. I suppose the most exciting moment occurred when Scylla and her destroyer escort was returning from a diversion to Spitzbergen where we had re-

A few ships were sunk but the Germans got a bit of their own medicine and thereafter treated the convoy with some respect. We had rescue ships available to pull survivors from the Arctic Ocean, a hideously cold place in which to find oneself! Most only lasted a few minutes before being frozen to death. I clearly recall Scylla taking a large number of survivors on board from the rescue ship, mainly American merchant seamen. One in particular remains in my memory, a tall bespectacled man very much in the "Uncle Sam" tradition. Within twenty minutes of coming aboard Scylla, and after a cup of hot soup, he was found with a bucket and mop cleaning out the sailors' bathroom!

HMS Scylla 1942

A member of crew on the snow-

During my time in Tyne, one of the interesting people I met was the RC chaplain, one Father Christopher Shine of the Order of Friars Minor (Capuchin). He was a strange but kind man who held court in his cabin to a wide range of the ship's company of all ranks. We used to have long and interesting arguments and discussions on all sorts of subjects and he was certainly the first priest to teach me the basics of philosophy. Like so many of his kind he liked the bottle, and was happy to share it with the favoured few, although in the fleet this was strictly verboten!

My trip to North Russia in the destroyer Onslaught was interesting. The captain was a most charismatic character who was known to his sailors as Joe ‘Mile-

My last sea trip before leaving the Tyne was another trip to North Russia in the destroyer Intrepid. We went first to Iceland to Hvalfjord and then to Akureyri where we picked up the convoy. The trip was unremarkable except that my temporary Divisional Officer was a young RNVR Lieutenant named Gerald Coombes. He was most unlike the average regular RN officer and was in consequence rather a lonely young man. He did however have a gramophone and a good selection of classical music which we both liked and shared. We remained in touch for a number of years after the war and Gerald will appear again later in this narrative. The only other thing which I remember of this trip was that after leaving Iceland on the return trip to Scapa we hit a freak sea which dropped the whole forecastle about half an inch. Two large stanchions which supported the lower forecastle mess deck bent outwards from the pressure and you have never seen a mess deck full of sailors empty so fast!

Towards the end of my time in the Tyne I was recommended to become what was called a CW (Commissions & Warrants) Candidate. This meant that I had to spend further sea time learning the rudiments of seamanship and then sit a Board which would decide if I was fit to go on to train as a prospective RN Sub-

HMS Tyne

From memory, I became a Quarterdeckman, lived in one of the forward seamen's messes, acted as an Oerlikon loader on the boat deck in action, and kept watch as a Bridge Messenger when at sea. It was all very new to me, and the few of us who were CW candidates took a fair amount of ribbing from the rest of the troops (who didn't really like the idea of promotion from the lower deck to the wardroom). I remember that when the QM piped “Hands to Dinner” there was always some wag who added “CW Candidates to Lunch!”

HMS Belfast was the flagship of the 10th Cruiser Squadron and flew the flag of CS10. Shortly after I joined her, the flag officer changed and no less a person than my old admiral Bob Burnett took over as CS10. Life in a ship of some 13,000 tons was very different from that spent bucketing around the ocean in a destroyer. As well as one's normal duties as a seaman scrubbing decks and polishing brightwork, the CW candidates had also to learn the basics of navigation and mathematic, taught by the resident ‘Schooly’ (in our case by a kindly Scottish Instructor Lieutenant).

After a few weeks in my new ship who should arrive on board, also as a CW candidate, but my old sparring partner Bob Camplin. This was wonderful and went a very long way to making this strange new life in the Belfast bearable. We shared a mess, shared our schooling, and were both employed as Bridge Messengers at sea (though in different watches). Being a big ship, we were able to operate in three watches (Red, White and Blue), far less wearing than our life in destroyers. Catering was handled centrally so that the entire ship’s company got the same diet. We served in this ship until just before D-

Most of our time was spent backing up the North Russian convoys (though not often in the close escort) but still enduring the snow and ice of the Arctic. So it happened that Belfast found herself in the Russian port of Polyarno in the Kola Inlet just before Christmas 1943. On Christmas Eve, by day, a Russian boat arrived alongside Belfast, there was a great clatter up the port gangway, then a Russian officer in a fur cap saluted the Officer of the Watch, announced “From my Admiral to yours” and departed, leaving the OOW with a live reindeer wandering about the quarterdeck!! For a while there was a bit of consternation, then “Port watch of seamen lay aft to secure reindeer” was piped and eventually the poor beast was caught, tethered and lead into the port hangar where it was given a temporary billet and water to drink. Great excitement! That afternoon Bob and I and the other two CW candidates were doing schoolwork at the other end of the port hangar from the reindeer. At this point, the Commander, one Philip Welby-

Shortly after, we put to sea, covering convoy JW 55B, and had the Christmas of 1943 at sea in the Arctic. In company were the cruisers Norfolk (Bob Camplin's old ship) and the Sheffield. Meantime, far to the east, a force including the battleship Duke of York and the cruiser Jamaica. They were at sea because there was strong reason to believe that the German pocket battleship Scharnhorst other units of the German fleet from Norway might be at sea and become a menace to the convoys.

HMS Belfast and crew October 1943

On the morning of Boxing Day, our three cruisers made brief contact with the Scharnhorst and there was an exchange of gunfire and a shell from Norfolk put one of the German's radars out of action. Bob Burnett again put us between the German and her base. Meanwhile to the east Bruce Fraser and the Duke of York was busting his boilers to get into position where he could prevent the Scharnhorst from breaking back to Norway. At midday, our cruiser force again made contact with the German and exchanged fire. This time the Norfolk received two hits, one of which put one of her gun turrets out of action. For the rest of the afternoon we shadowed the German ship at high speed using radar and kept the Commander in Chief, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser in the picture. Finally, at about 4 p.m. the Duke of York made radar contact with the Scharnhorst and the fight was on.

My recollection of the day was of being called to Action Stations in the morning, then after the midday skirmish feeling the throbbing of huge engines as we steamed at full speed to keep in touch. My action station was on the boat deck standing by one of the Oerlikon guns (not very effective against a battleship!!). There was one moment in the evening when the Scharnhorst burst a salvo of ‘starshell’ above us and as we stood in this eerie light, I remember feeling oh so very exposed waiting for some high explosive to arrive! Apart from a hole in one funnel from a near miss, we were not hit. The final hours were confusing. Destroyers had slowed the German down with torpedo hits, all of us were firing at her as opportunity allowed. Just before the end at about 7 p.m. Jamaica and Belfast made torpedo attacks (none hit) and later the destroyers closed in and finished her off with torpedoes.

Heavily muffled seamen hack the ice from HMS Belfast's forecastle, November 1943

When it was all over there were only 36 German survivors, all ratings, picked up out of a crew of over 1900. Her escort of German destroyers had been ordered back to Norway much earlier in the day.

As so often happens, it is the trivia of life which one so often remembers. After Scharnhorst was confirmed as sunk, the Commander in Chief ordered the traditional "Splice the Mainbrace", in other words, issue all hands with an extra tot of rum. I was under age to draw any rum and so qualified for a free glass of lime juice! It was freezing cold and I was furious!! The other very sad thing was that the terrible crash of 8-

The next six months were spent in Scapa or at sea in northern waters covering the Russian convoys. For a change, we also covered a force of aircraft carriers who launched a raid by Buccaneer aircraft against the Tirpitz in Altenfjord. I remember going to a splendid show in the Scapa theatre where a young John Mills did the St Crispin speech from Henry V and Bernard Miles did a splendid monologue leaning on an enormous cartwheel, which started with “Oi 'ad this old wheel gimme -

1944

Then in early June 1944, the CW Candidates were drafted temporarily to the Duke of York to go before a Board to assess whether or not we were suitable for further training to be officers. In the meantime, the Belfast sailed for Portsmouth.

The Upper Yardmen's Board was a pretty nerve wracking affair since so much of one's future hung on it. The President was Duke of York's Captain, the Honourable Sir Guy Russell. He was supported by a most unpleasant Commander (who we nicknamed the ‘Screaming Skull’) and another senior officer of whom I have very little recollection. There were two Boards sitting on the fleet, ours and another in the cruiser Jamaica presided over by her rather unpleasant Captain Hughes-

Scharnhorst

Sinking of the ‘Scharnhorst’, 26 December 1943

Charles E. Turner. National Maritime Museum

The Board completed, we were sent by rail to rejoin the Belfast in Portsmouth (at the other end of the country). It was a long and dreary wartime train journey and we arrived in London at 6 a.m. on 6th June 1944, the historic D-

So, though we didn't make it to France on D-

This website is owned by The Arctic Convoy Club of New Zealand © 2004 -

Footnote: HMS Scylla

On 23 June 1944 HMS Scylla was badly damaged by a mine off Normandy and declared a constructive total loss. Although towed to Portsmouth, she was not disposed of until 1950, after use as a target between 1948 and 1950. She arrived at Thomas W Ward on 4 May 1950 for breaking up. HMS Scylla served with the Home Fleet on Arctic Convoy duties and was present at the Normandy landings as flagship of the Eastern Task Force.

Peter Holt passed away on 11 December 2019

| About Us |

| About Arctic Convoys |

| Convoy Kiwis |

| Greetings Exchange |

| Affiliations |

| Links |

| Topical Items |

| Decorations |

| Membership |

| My Story |

| Newsletter |

| Online Application Convoy Membership |

| Convoy Numbers |

| Merchant Navy Ships |

| Royal Fleet Auxiliary |

| Royal Navy Ships A - B |

| Royal Navy Ships C - F |

| Royal Navy Ships G - L |

| Royal Navy Ships M - O |

| Royal Navy Ships P - T |

| Royal Navy Ships U - Z |

| Obituaries |

| Wellington Memorials |